BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management company, has described tokenization as the most critical market upgrade since the early internet.

On the other hand, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) describes it as a volatile, untested architecture that can amplify financial shocks at machine speed.

Both institutions look at the same innovation. Yet the distance between their conclusions reflects the most consequential debate in modern finance: whether tokenized markets will reinvent global infrastructure or reproduce its worst vulnerabilities at new speed.

The institutional divide over tokenization

On December 1 op-ed for The Economist, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink and COO Rob Goldstein argued that recording asset ownership in digital ledgers is the next structural step in a decades-long arc of modernization.

They viewed tokenization as a financial leap comparable to the advent of SWIFT in 1977 or the shift from paper certificates to electronic trading.

The IMF, on the other hand warned a recent explainer video pointed out that tokenized markets can be prone to sudden crashes, liquidity fractures and smart-contract domino cascades that turn local failures into systemic shocks.

The division over tokenization stems from the fact that the two institutions operate under very different mandates.

BlackRock, which has already rolled out tokenized funds and dominates the spot ETF market for digital assets, is approaching tokenization as an infrastructure play. Its motivation is to expand access to the global market, compress settlement cycles to “T+0” and broaden the investable universe.

In that context, blockchain-based ledgers seem like the next logical step in the evolution of financial plumbing. This means that the technology offers a way to eliminate costs and latency in the traditional financial world.

However, the IMF operates from the opposite direction.

As a stabilizer of the global monetary system, it targets the difficult-to-predict feedback loops that arise when markets operate at extremely high speed. Traditional finance relies on delays in the settlement of net transactions and maintains liquidity.

Tokenization introduces instant settlement and composability of smart contracts. That structure is efficient during calm periods, but can spread shocks much faster than human intermediaries can respond.

Rather than contradicting each other, these perspectives reflect different layers of responsibility.

BlackRock is tasked with developing the next generation of investment products. The IMF’s job is to identify the fault lines before they spread. Tokenization is at the intersection of that tension.

A technology with two futures

Fink and Goldstein describe tokenization as a bridge “built on both sides of a river,” connecting traditional institutions with “digital-first” innovators.

They argue that shared digital ledgers can eliminate slow, manual processes and replace disparate settlement pipelines with standardized rails that participants in different jurisdictions can instantly verify.

This view is not theoretical, although the data must be carefully analyzed.

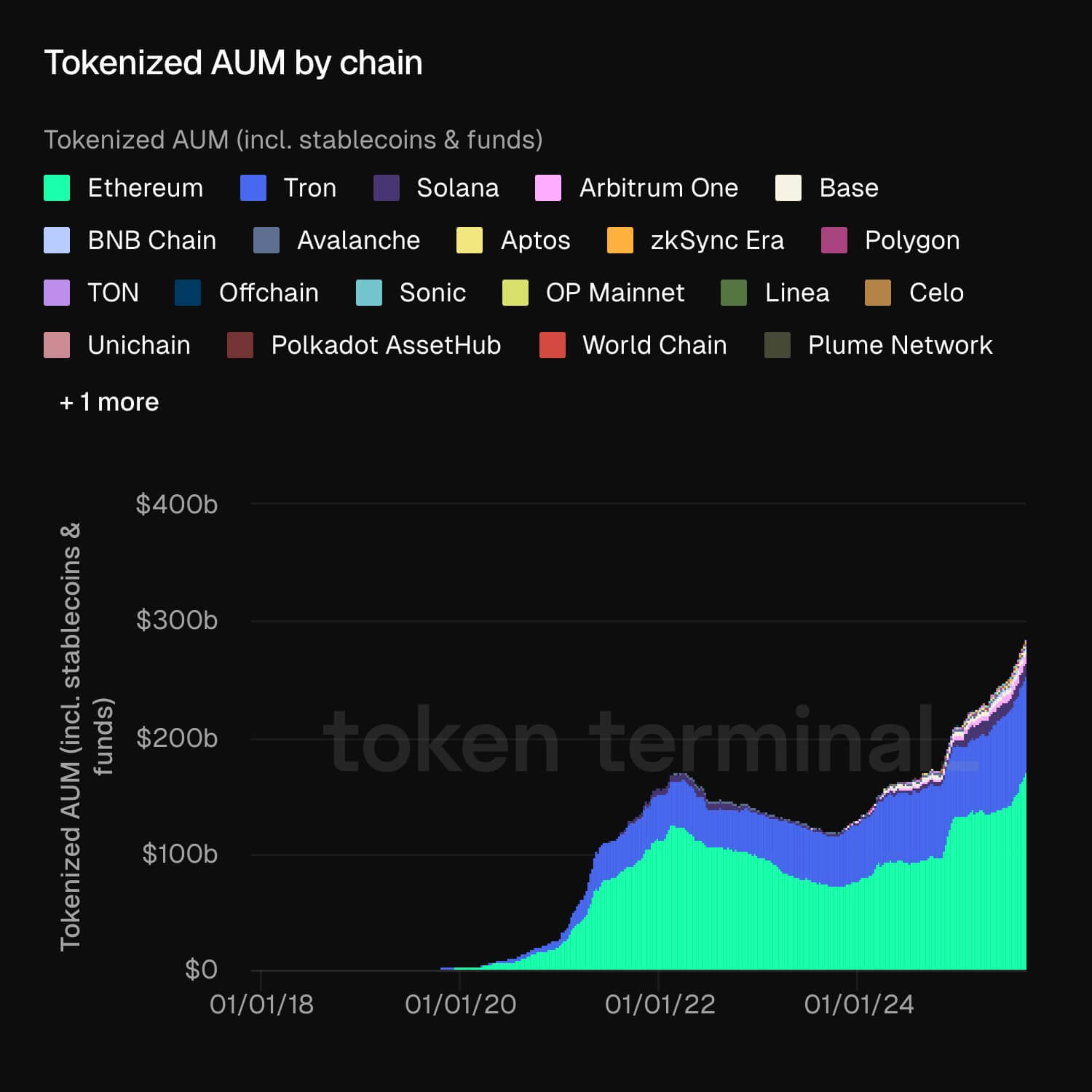

According to Token Terminal, the broader tokenized ecosystem is approaching $300 billion, a figure strongly anchored by dollar-pegged stablecoins such as USDT and USDC.

The actual test, however, lies in the roughly $30 billion in regulated real-world assets (RWAs), such as tokenized Treasuries, private credits and bonds.

These regulated assets are no longer limited to pilot programs.

Tokenized government bond funds such as BlackRock’s BUIDL and Ondo’s products are now live. At the same time, precious metals have also entered the chain, with significant volumes in digital gold.

The market has also seen fractionalized real estate equities and tokenized private credit instruments expand the investable universe beyond listed bonds and equities.

In light of this, forecasts for this sector range from optimistic to astronomical. Reports from companies like RedStone Finance project a “blue sky” scenario in which on-chain RWAs could reach $30 trillion by 2034.

Meanwhile, more conservative estimates from McKinsey & Co. suggest that the market could double as funds and government bonds migrate to blockchain rails.

For BlackRock, even the conservative case represents a multi-trillion dollar restructuring of the financial infrastructure.

Yet the IMF sees a parallel, less stable future. His concern focuses on the mechanics of atomic settlements.

In today’s markets, transactions are often ‘netted’ at the end of the day, meaning banks only have to settle the difference between what they bought and sold. An atomic settlement requires that each transaction be fully funded immediately.

In stressful circumstances, demand for pre-funded liquidity can increase sharply, causing liquidity to evaporate precisely when it is most needed.

If automated contracts then lead to liquidations “like falling dominoes,” a local problem could become a systemic cascade before regulators even receive the warning.

The liquidity paradox

Part of the excitement around tokenization stems from where the next cycle of market growth might come from.

The last crypto cycle was characterized by speculation based on memecoins, which generated high activity but drained liquidity without expanding long-term adoption.

Tokenization proponents argue that the next expansion will be driven not by retail speculation, but by institutional return strategies, including tokenized private credits, real debt instruments, and enterprise-grade vaults that deliver predictable returns.

In this context, tokenization is not just a technical upgrade, but a new liquidity channel. Institutional allocators facing a limited traditional return environment may migrate to tokenized credit markets, where automated strategies and programmable settlement can deliver higher, more efficient returns.

However, this future remains unrealized because large banks, insurers and pension funds face legal restrictions.

For example, the Basel III Endgame Rules assign punitive capital treatment to certain digital assets classified as ‘Group 2’, discouraging exposure to tokenized instruments unless regulators clarify the distinction between volatile cryptocurrencies and regulated tokenized securities.

Until that boundary is defined, the “wall of money” remains more potential than reality.

Moreover, the IMF states that even if the funds arrive, they have a hidden influence.

A complex stack of automated contracts, collateralized debt positions and tokenized credit instruments can create recursive dependencies.

During periods of volatility, these chains can unwind more quickly than the risk engines they were designed to handle. The very features that make tokenization attractive, such as immediate settlement, the ability to compose and global access, create feedback mechanisms that can increase stress.

The tokenization question

The debate between BlackRock and the IMF is not about whether tokenization will integrate into global markets; that is already the case.

It is about the process of that integration. One path provides a more efficient, accessible, globally synchronized market structure. The other anticipates a landscape in which speed and connectivity create new forms of systemic vulnerability.

In that future, however, the outcome will depend on whether global institutions can converge on coherent standards for interoperability, disclosure and automated risk controls.