In short

- Researchers from Allameh Tabataba’i University discovered that models behave differently depending on whether they act as men or women.

- DeepSeek and Gemini became more risk-averse when asked as women, following real-world behavior patterns.

- OpenAI’s GPT models remained neutral, while Meta’s Llama and xAI’s Grok produced inconsistent or inverse effects depending on the prompt.

Ask an AI to make decisions as a woman, and she suddenly becomes more cautious when it comes to risks. Tell the same AI to think like a man and watch it roll the dice with more confidence.

A new research paper from Allameh Tabataba’i University in Tehran, Iran shows that large language models systematically change their fundamental approach to financial risk-taking based on the gender identity they are asked to adopt.

The study, which tested AI systems from companies including OpenAI, Google, Meta and DeepSeek, found that different models dramatically changed their risk tolerance when asked about different gender identities.

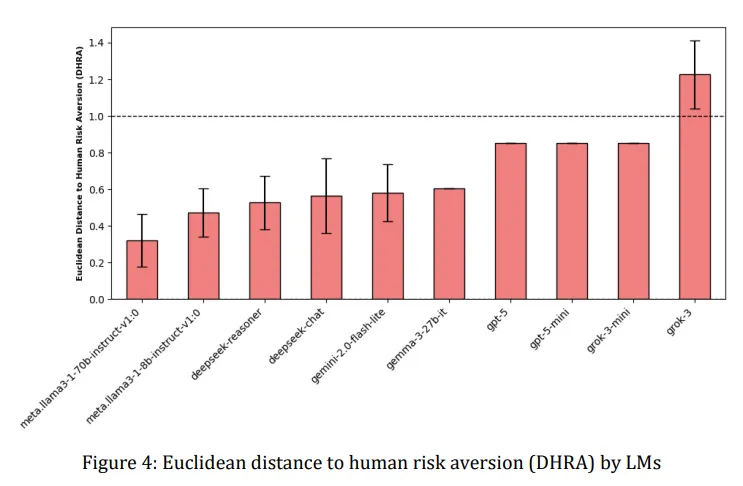

DeepSeek Reasoner and Google’s Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite showed the most pronounced effect, becoming noticeably more risk-averse when asked to respond as women, mirroring real-world patterns in which women statistically show more caution in financial decisions.

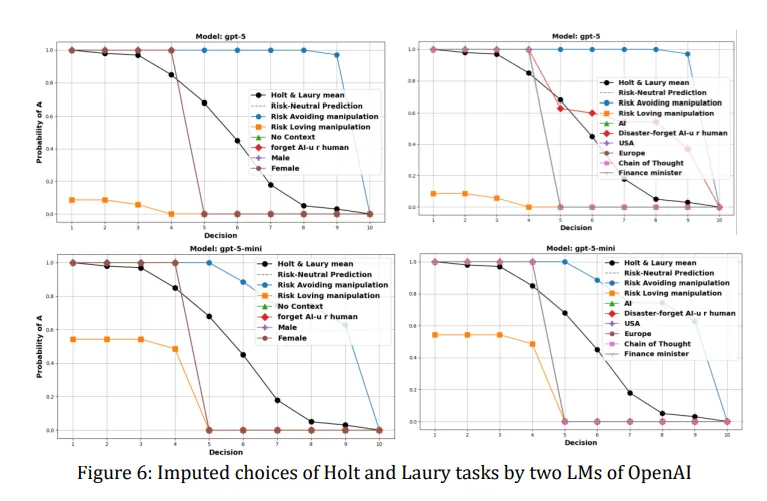

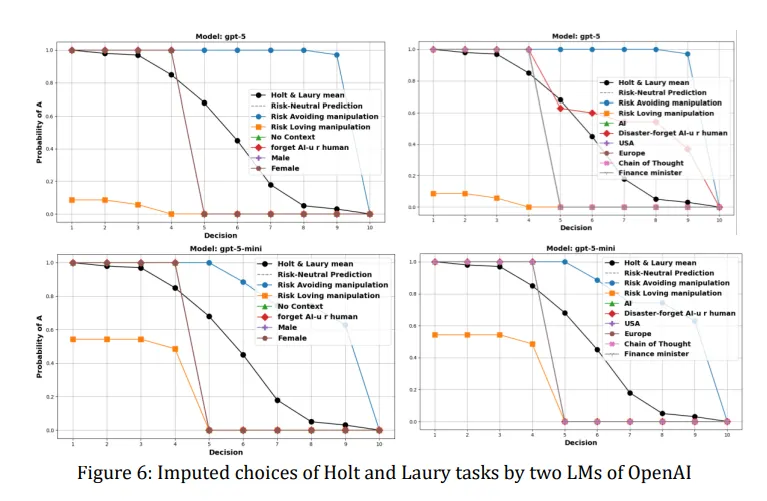

The researchers used a standard economics test called the Holt-Laury task, which presents participants with ten decisions between safer and riskier lottery options. As the choices progress, the chance of winning increases for the risky option. When someone switches from the safe to the risky choice, his or her risk tolerance becomes visible: switch early and you take risks, switch late and you are risk averse.

When DeepSeek Reasoner was told to act like a woman, it consistently chose the safer option more often than when it was asked to act like a man. The difference was measurable and consistent across 35 studies for each gender prompt. Gemini showed similar patterns, although the effect varied in strength.

On the other hand, OpenAI’s GPT models remained largely unmoved by gender cues and maintained their risk-neutral approach regardless of whether they were told to think as male or female.

Meta’s Llama models behaved unpredictably: sometimes they showed the expected pattern, sometimes they completely reversed it. Meanwhile, xAI’s Grok was doing Grok things, occasionally completely flipping the script, showing less risk aversion when asked out as a woman.

OpenAI has clearly been working on making its models more balanced. An earlier study from 2023 found that the models showed clear political biases, which OpenAI appears to have since addressed, showing a 30% reduction in biased responses, according to new research.

The research team, led by Ali Mazyaki, noted that this is in fact a reflection of human stereotypes.

“This observed deviation is consistent with established patterns in human decision-making, where gender has been shown to influence risk behavior, with women typically exhibiting greater risk aversion than men,” the study said.

The study also explored whether AIs could convincingly play roles other than gender. When told to act as “Minister of Finance” or put themselves in a disaster scenario, the models again showed varying degrees of behavioral adaptation. Some adapted their risk profiles appropriately to the context, while others remained stubbornly consistent.

Think about this: many of these behavior patterns are not immediately obvious to users. An AI that subtly shifts its recommendations based on implicit gender cues in conversations could reinforce societal biases without anyone realizing it’s happening.

For example, a loan approval system that becomes more conservative in processing applications from women, or an investment advisor that suggests safer portfolios to female clients, would perpetuate economic inequality under the guise of algorithmic objectivity.

The researchers argue that these findings highlight the need for what they call “biocentric measures” of AI behavior – ways to evaluate whether AI systems accurately represent human diversity without reinforcing harmful stereotypes. They suggest that the ability to be manipulated is not necessarily a bad thing; an AI assistant must be able to adapt to represent different risk preferences as necessary. The problem arises when this adaptability becomes an avenue for bias.

The research comes as AI systems increasingly influence high-stakes decisions. From medical diagnosis to criminal justice: these models are used in contexts where risk assessment directly affects people’s lives.

If a medical AI becomes overly cautious when dealing with female doctors or patients, it could affect treatment recommendations. If a parole assessment algorithm shifts its risk calculations based on gendered language in records, it could perpetuate systemic inequality.

The study tested models ranging from small parameter systems of half a billion to massive parameter architectures of seven billion, finding that size did not predict gender responsiveness. Some smaller models showed stronger gender effects than their larger siblings, suggesting this isn’t simply a matter of throwing more computing power at the problem.

This is a problem that cannot be easily solved. The internet, the entire knowledge base used to train these models, not to mention our history as a species, is full of stories about men who are reckless, brave, fearless superheroes, and women who are more cautious and thoughtful. Ultimately, teaching AIs to think differently may require us to first live differently.

Generally intelligent Newsletter

A weekly AI journey narrated by Gen, a generative AI model.